Pattern making was never meant to be fast. And it was never meant to be simple.

It began as a necessity — a way to give structure to the body, to protect it, to allow it to move. Over time, it became something far more demanding: a discipline built on observation, trial, failure, and constant adjustment.

In its earliest forms, everything was direct and physical. Fabric, hands, basic lines. Not because imagination was limited, but because each era works with the tools and realities it has. Clothing needed to function first. Expression came later.

As fashion evolved, so did the way we looked at the body. And every shift in silhouette, every change in aesthetic or lifestyle, forced the craft behind garments to evolve alongside it.

Fashion has always moved between extremes — control and freedom, structure and softness, excess and restraint. Each transition demanded new ways of constructing garments.

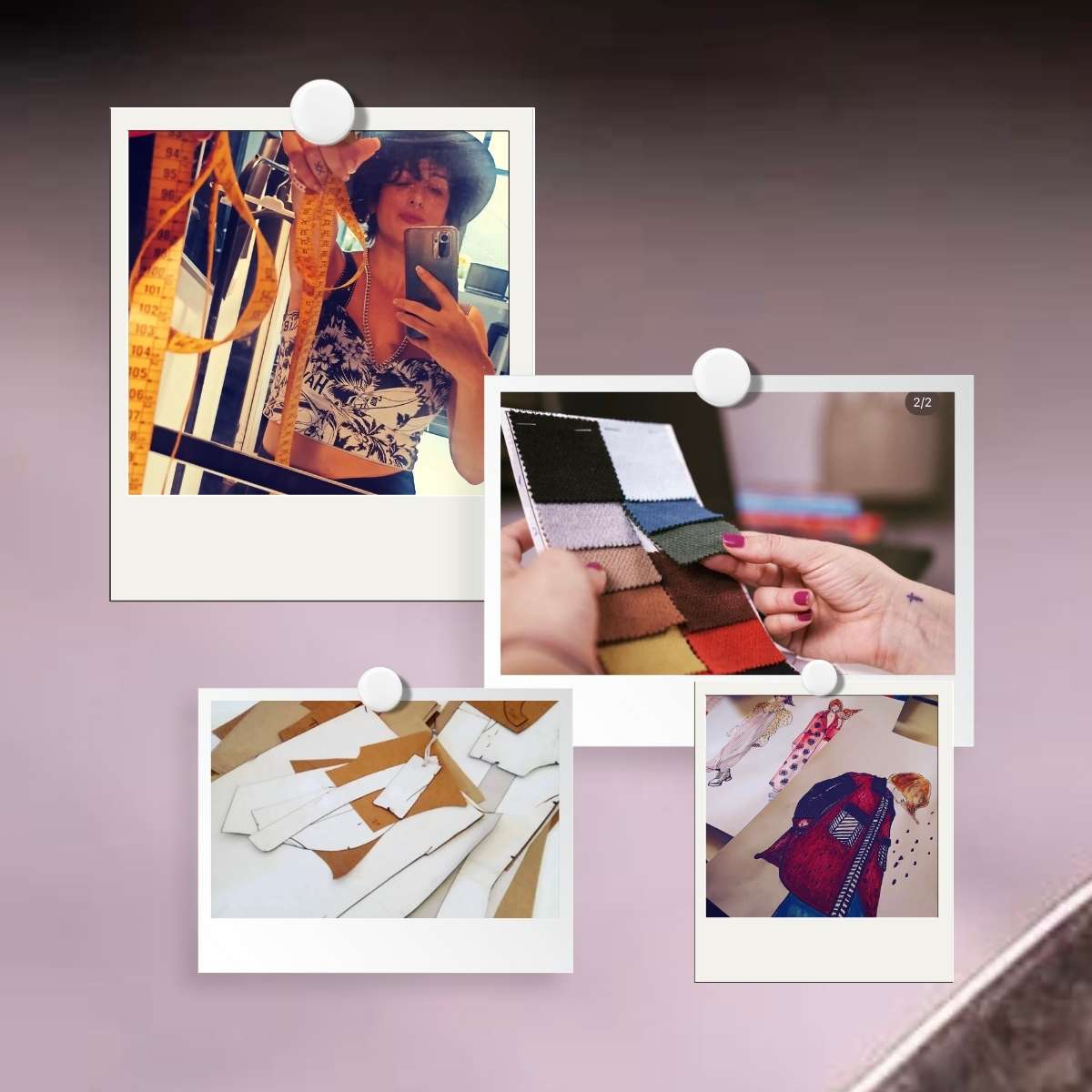

This evolution never followed formulas. It happened through people who observed closely, tested relentlessly, and learned through mistakes. Pattern makers relied on classical foundations, not as rigid rules, but as a starting point — something to question, bend, and rework.

Because no two designs ask for the same handling.

And no garment allows you to work on autopilot.

Anyone who has worked seriously with patterns knows this: learning never moves in a straight line. This craft is a long journey, and one of its most humbling truths is that the more you learn, the more you realise how much you still don’t know.

There are moments of confidence — when you feel experienced, capable, secure. And then a new design appears. A different construction. A fabric that behaves unexpectedly. Suddenly, past solutions no longer apply.

Every new pattern demands a different approach.

A different balance of technique, experience, problem-solving and imagination.

Nothing is automatic. Everything requires intention.

Digital tools have undeniably changed the workflow. Digital pattern making and 3D sampling allow faster experimentation, fewer physical samples, and more flexibility during development. They support the process, especially within modern fashion design pipelines.

Read more here.

But no matter how advanced technology becomes, there will always be garments that cannot be fully resolved on a screen.

Some designs require paper, rulers, pencils.

They require time at the table, corrections made by hand, and decisions that only emerge through physical interaction with the pattern.

Not because technology is insufficient — but because certain garments demand proximity. They demand patience. They demand presence.

This interview its interesting.

This is where traditional methods and digital tools coexist, not in opposition, but as part of the same design process.

It doesn’t follow trends in the way fashion does — but it doesn’t remain static either.

It evolves as bodies change.

As aesthetics shift.

As materials, tools, and production realities transform.

Each era reshapes how patterns are approached, tested, and constructed. And each person working with them is required to evolve as well — technically, creatively, and mentally.

Because this is not a skill you “complete.”

It keeps you alert. It challenges your assumptions. Sometimes, it forces you to unlearn what you thought was certain.

And maybe that is why it remains essential.

Because no matter how tools change, this discipline will always require thought, time, experience, and imagination. Some garments will always ask for the hand. Some answers will never come instantly.

And that is not a limitation.

It is the reason the craft endures.